Businesses follow a general growth trend but, much like people, each company is unique and follows its own trajectory. Some grow large, others remain small, some die young while others live over centuries. Again, much like people, a few have long and happy lives, free of tragedies, while others experience accidents and near-death experiences.

That’s where the concept of turnaround comes in. When facing hard times, the risk of slipping into a downward spiral is high and, if not properly managed, typically ends in the liquidation or sale of a company.

In the last few years, geopolitical conflicts and issues, opposing governmental recovery policies, and other macroeconomics factors have led to heavy fluctuations in the international markets, affecting equally currencies, raw materials, natural resources, and, as a result, companies.

Many countries in Latin America, for example, have seen a steep devaluation of their currencies along with a constant rising – and sudden drop – in oil prices. As a more specific example, the Mexican Peso went from around MXP 13.10:$1 in January 2014 to MXP 16.73:$1 now.

Even more extreme, Colombia saw the otherwise stable Colombian Peso jump from an average of COP 1,800-1,900 for $1 during 2010-2013 to a high of COP 3,247 for $1 on September 15, 2015 (right now $1 is exchanged for COP 3,042). This basically means that all goods imported in USD cost roughly 65% more Colombian Pesos now than it did 2 years ago. Add to it variable tariffs on the import of some goods from countries/goods without free trade agreement in place, and you may need to add another 50%-60% on top of your costs.

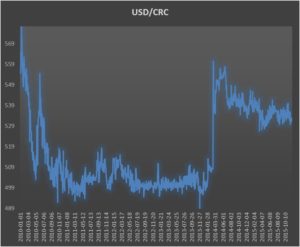

Want another example? How about Costa Rica and its Colon, the currencies went from trading as high as CRC 577 for $1 to a low of CRC 492 for $1 in 2010. After 4 years of a relative stable exchange rate, it jumped back up to the mid/high 500’s in 2014 and stayed there, currently at an average, for the last 5 months, of CRC 546 for $1. Now consider that in Costa Rica, there’s a mandatory wage re-evaluation twice a year based on the evolution of the consumers’ purchasing power. So, if you’re an importer, you’re getting hit with the exchange rate eating up your margins and then, if you’re not dead yet, with a mandatory increase in wages. If you’re Intel, it’s OK, you just move on to some cheaper market. If you’re a local entrepreneur, you’d better have some liquidity available and a good stomach, ’cause you’re in for quite a ride.

Want another example? How about Costa Rica and its Colon, the currencies went from trading as high as CRC 577 for $1 to a low of CRC 492 for $1 in 2010. After 4 years of a relative stable exchange rate, it jumped back up to the mid/high 500’s in 2014 and stayed there, currently at an average, for the last 5 months, of CRC 546 for $1. Now consider that in Costa Rica, there’s a mandatory wage re-evaluation twice a year based on the evolution of the consumers’ purchasing power. So, if you’re an importer, you’re getting hit with the exchange rate eating up your margins and then, if you’re not dead yet, with a mandatory increase in wages. If you’re Intel, it’s OK, you just move on to some cheaper market. If you’re a local entrepreneur, you’d better have some liquidity available and a good stomach, ’cause you’re in for quite a ride.

I know many are thinking that these things only happen to emerging economies and developing countries… or not. Yes, these 2 links are about the Euro and Swiss Franc’s recent plummeting… need I say more?

Wasn’t this post about turnarounds?

Let’s take a real life example. The company – let’s call it Target – had solid growth year over year for the past 5 years. It distributes a world-recognized brand that is market leader in tens of markets worldwide. Demand for the products is ever-growing and margins were good… that is until 2014. With the currency devaluing, importing in USD and selling in local currency resulted in a heavy hit on the company’s finances. In the meantime, the customs’ variable tariffs stepped in to help protect the local players against the staggering prices of raw materials imports, jacking up the import duties for that product class from neighboring country over the 50% mark.

Let’s take a real life example. The company – let’s call it Target – had solid growth year over year for the past 5 years. It distributes a world-recognized brand that is market leader in tens of markets worldwide. Demand for the products is ever-growing and margins were good… that is until 2014. With the currency devaluing, importing in USD and selling in local currency resulted in a heavy hit on the company’s finances. In the meantime, the customs’ variable tariffs stepped in to help protect the local players against the staggering prices of raw materials imports, jacking up the import duties for that product class from neighboring country over the 50% mark.

Our target company, which unfortunately imported its products from that very same neighboring country suddenly saw its margins contract, albeit a price increase to the end consumer. Hit twice as hard by macroeconomics conditions out of its control, it sees its cash balance decline to dangerously low levels. In the meantime, its main competitor, who imports from the US with no duties as covered by the Free Trade Agreement in place, thrives in the market, eating up the shelf space left empty by Target, which, by now is no longer able to import more product due to its financial distress.

Fast forward a few months and you now have a Target in default with its main providers, selling at all cost the inventory it still has available, which, naturally, is far from being the ideal product mix, to be able to meet its monthly obligations with employees and banks. In the market, the once praised brand became that brand that used to be. Customer, seeing an increased number of SKU in Out of Stock mode, slowing shift away for Target altogether, preferring, instead, the competition – and its stable product supply.

That’s where a new investor comes in, and more specifically one with a turnaround, high risk / high rewards inclination. The idea is relatively simple: Inject capital in Target to wipe off any debt with its providers, restock inventories and regain shelf space in the market, potentially subsidizing the margins at first while the whole duty situation comes back to normal levels… or while we setup a change in the supply chain to import from a free trade zone. Since the brands distributed are proven brands with global presence and image, there should be low risk there… that is, other than for the relationship and trust between Target and its providers needs to be restored.

That’s where a new investor comes in, and more specifically one with a turnaround, high risk / high rewards inclination. The idea is relatively simple: Inject capital in Target to wipe off any debt with its providers, restock inventories and regain shelf space in the market, potentially subsidizing the margins at first while the whole duty situation comes back to normal levels… or while we setup a change in the supply chain to import from a free trade zone. Since the brands distributed are proven brands with global presence and image, there should be low risk there… that is, other than for the relationship and trust between Target and its providers needs to be restored.

Now, this plan could, indeed, work if the company still has enough of a presence in the market and if its internal infrastructure remains solid enough. More broadly, on paper, it works… if all the stars align. However, there are many challenges to take into account. For example, and in no particular order, I can think of:

- When dark times come, it is not uncommon that the best elements smell it from afar and move on, in that case, the salespeople, primarily responsible for the much-needed high demand to push inventory rotation.

- What happens if the currency continues to go down and tariffs stay at all time high levels? …and no, “it’s so low, there’s no way it can get any worse” is NOT a correct answer.

- In the absolute best scenario, there’s a 30 day confirmatory due diligence period from the point of agreement and, say, a 60 day turnaround time from order to delivery of products with suppliers. That’s 3 months between agreeing on a general transaction price and structure and hitting the road with trucks full of products. Three months, that is, under ideal scenarios and assuming that legal closing documents are written and negotiated in the same 30 day timeframe of the Due Diligence. That’s 3 months for Target’s competitors to continue to poach its best employees and fill up its empty shelves, 3 months of paying payroll and outstanding debt without meaningful sales to back those payments, 3 months of consumers not being able to find the products in the market and either switching brands or buying elsewhere (thank you e-commerce)… basically, three long months to potentially finish to kill that company.

- What if it’s too late? Maybe Customers lost all trust in Target and won’t come back. Maybe Consumers switched in mass to competing brands and like it so much that they won’t go back. Maybe Target could not last that last mile, defaulted, and the banks are now in possession. Maybe the Suppliers seeing the company in default for various months went on to execute plan and brought it a new distributor or set itself up to handle that market in-house…

Bottom line, the big question, in this specific case is whether the company is salvageable or if you’re coming in too late.

Various institutional funds focus almost exclusively on turnaround situations. Of the top of my head, I can think of Sun Capital Partners, KPS Capital Partners, or Carlson Private Equity but a plethora of such groups exist out there and it’s understandable, although risks are high, rewards can be even higher. If you invest all you have in 1 failing company, you’re taking an abnormally high level of risk and are, most probably, not sleeping well at night. But if you spread your risks over a broad portfolio of distressed opportunities (ailing companies), then the success of one will balance the failure of another. In the end, it’s pretty close to a VC’s approach.

If you have enough capital and only commit a – relatively – small amount to a portfolio of distressed opportunities, then you can afford to take some risks and see what sticks… However, if you’re not a turnaround-focused fund and still decide to get involved in such a transaction, then you’re either a true hardcore gambler or you’re someone who understands the industry of the target and aren’t afraid to get your hands dirty.

Going back to the example above, the likelihood that a luxury boat manufacturer in Europe or a mining behemoth in Russia decide to invest – and run – a distressed fast-moving consumer goods distributor in Latin America is, humm, slim. However, an entrepreneur from the region who understands the sector, the specifics of the country, and has other businesses somewhat aligned with this one might see it as a great opportunity to diversify its portfolio and to generate significant value doing so.

Why? Maybe because (s)he knows what to expect and how to overcome those challenges. It doesn’t mean that this investment is risk free, but it sure is less risky for the Latin American entrepreneur in the space than it is for the European boat manufacturer or the Russian mining oligarch. This risk becomes even slimmer for the LatAm entrepreneur if (s)he has some extra dry powder to commit to the project going in. This way, delays in recovering sales volumes and other potential undesired situations that may arise will not result in the same outcome the company is experiencing today: near death experience due to cash flow problems.